| Operation Barbarossa remains the largest military operation, in terms of manpower, area traversed, and casualties, in human history. The failure of Operation Barbarossa resulted in the eventual defeat of Nazi Germany and is considered a turning point for the Third Reich. Most importantly, Operation Barbarossa opened up the Eastern Front, which ultimately became the biggest theater of war in world history. Operation Barbarossa and the areas which fell under it became the site of some of the largest and most brutal battles, deadliest atrocities, terrible loss of life, and horrific conditions for Soviets and Germans alike - all of which influenced the course of both World War II and the 20th century history. While this film of one of the epic struggles of WWII is over 50 years old, it still delivers the drama of the battle fought by Russian soldiers and sailors to defend Leningrad. Codenamed "Operation Barbarrosa" by Hitler, the battle was truly horrific. This documentary, The Great Battle of the Volga, focuses on the bravery and suffering of the Russian soldiers as they endure the tremendous attack by the well-equipped German army. That they could regroup and fight back with such ferocity is depicted, along with the terrible destruction caused by the Germans | Operation Barbarossa |

|  |

| In calling off Operation Sea Lion, Adolf Hitler, the Supreme Commander of the world's most powerful armed forces, had suffered his first major setback. Nazi Germany had stumbled in the skies over Britain but Hitler was not discouraged. In the past, he had repeatedly overcome setbacks of one sort or another through drastic action elsewhere to both triumph over the failure and to move toward his ultimate goal. Now it was time to do it again. All of Hitler's actions in Western Europe thus far, including the subjugation of France and the now-failed attack on Britain, were simply a prelude to achieving his principal goal as Führer, the acquisition of Lebensraum (Living Space) in the East. He had moved against the French, British and others in the West only as a necessary measure to secure Germany's western border, thereby freeing him to attack in the East with full force. For Hitler, the war itself was first and foremost a racial struggle and he viewed all aspects of the conflict in racial terms. He considered the peoples of Western Europe and the British Isles to be racial comrades, ranked among the higher order of humans. The supreme form of human, according to Hitler, was the Germanic person, characterized by his or her fair skin, blond hair and blue eyes. The lowest form, Hitler believed, were the Jews and the Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe, including the Russians. All of this had been outlined in his book, Mein Kampf, first published in 1925. In it, Hitler stated his fundamental belief that Germany’s survival depended on its ability to acquire vast tracts of land in the East to provide room for the expanding German population at the expense of the inferior peoples already living there, justified purely on racial grounds. Hitler explained that Nazi racial philosophy “by no means believes in an equality of races…and feels itself obligated to promote the victory of the better and stronger, and demand the subordination of the inferior and weaker.” Therefore, in stark contrast to the battles so far in the West, Hitler intended the quest for Lebensraum in the East to be a "war of annihilation" utilizing the might of the German Army and Air Force against soldiers and civilians alike. In March of 1941, he assembled his top generals and told them how their troops should behave: “This struggle is one of [political] ideologies and racial differences and will have to be conducted with unprecedented, unmerciful and unrelenting harshness. All officers will have to rid themselves of obsolete ideologies…I insist absolutely that my orders be executed without contradiction." Hitler then ordered the killing of all Russian political authorities. "The [Russian] commissars are the bearers of ideologies directly opposed to National Socialism. Therefore the commissars will be liquidated. German soldiers guilty of breaking international law…will be excused.” His generals listened in silence to this command, known later as the Commissar Order. For his most senior generals, the utterances of their Supreme Commander posed a dilemma. They were mostly men of the old-school, born and raised in Imperial Germany, long before Hitler, amid traditional morals of bygone days. Now, they felt duty-bound to follow Hitler’s orders, no matter how drastic, since they had all sworn an oath of obedience to the Führer. But to comply, they would have to abandon time-honored codes of military conduct, considered obsolete by Hitler, which prohibited senseless murder of civilians. At the same time, they each owed a debt of gratitude to Hitler for restoring the Germany Army to greatness and for the slew of promotions bestowed upon them by the Führer in the wake of its continued success. Rank and privilege, and the immense prestige of holding the title of Colonel-General or Field Marshal in Hitler's Wehrmacht, had tremendous appeal for these men, Therefore, in the end, despite their misgivings, not one of them dared to speak up or refuse Hitler in regard to his war plans for Russia. Instead, they dutifully planned the invasion of Russia, knowing the attack would unleash an unprecedented wave of murder. The invasion plan for Russia was named Operation Barbarossa (Red Beard) by Hitler in honor of German ruler Frederick I, nicknamed Red Beard, who had orchestrated a ruthless attack on the Slavic peoples of the East some eight centuries earlier. Barbarossa would be Blitzkrieg again but on a continental scale this time, as Hitler boasted to his generals, "When Barbarossa commences the world will hold its breath and make no comment!" Set to begin on May 15, 1941, three million soldiers totaling 160 divisions would plunge deep into Russia in three massive army groups, reaching the Volga River, east of Moscow, by the end of summer, thus achieving victory. Facing them would be Stalin's Red Army, estimated by the Germans at 200 divisions. Although somewhat outnumbered by the Russians, Hitler believed they did not pose a serious threat and would fall apart just like their fellow Slavs, the Poles, did in 1939. Against an army of battle-hardened, racially superior Germans, the Russians would be finished in a matter of weeks, Hitler claimed. Most of his generals concurred, supported by recent evidence. They had watched with keen interest as Soviet Russia confidently invaded Finland in November 1939, only to see the Red Army disintegrate into a disorganized jumble amid embarrassing defeats at the hands of a much smaller blond-haired Finnish fighting force. Buoyed by Hitler and awash in their own arrogance, the generals confidently finalized the details of Operation Barbarossa as the bulk of the German troops and armor slowly moved into position in the weeks leading up to May 15. But as the invasion date neared, complications arose that upset the whole timetable. Hitler's old friend and chief ally, Benito Mussolini, leader of Fascist Italy, had foolishly tried to imitate the Führer and achieve battlefield glory for himself by launching a surprise invasion of Greece. British troops stationed in the Mediterranean then moved in to help the Greeks fend off the Italians. For Hitler, the very idea of British troops in Southern Europe was enough to keep him awake at night. Their presence was a threat to Germany's vulnerable southern flank, the region of Europe known as the Balkans, which also supplied most of Germany's oil. It would therefore be necessary to secure the Balkans before launching Barbarossa. To quickly achieve this, Hitler slipped back into a familiar role – the political master manipulator – forging overnight alliances with two Balkan countries, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. But in Yugoslavia, things unexpectedly spiraled out of control when the government, upon its alliance with Hitler, was immediately overthrown by its own citizens. Hitler was enraged by the news, perceiving it as a blow to his prestige. In a tirade, he ordered his generals to crush the country "as speedily as possible" and also ordered Göring's Air Force to obliterate the capital city, Belgrade, as "punishment." For the Luftwaffe, Belgrade was an easy target and they quickly turned it to rubble while killing 17,000 defenseless civilians. Meanwhile, beginning on Sunday, April 6, 1941, the Wehrmacht poured 29 divisions into the region, taking Yugoslavia by storm, then took Greece for good measure, forcing British troops there to make a hasty exit. Thus the Balkans were secured. However, these actions took nearly five weeks and caused a lot of wear and tear on tanks and other armored equipment needed for the Russian campaign. July 1941. A confident looking Hitler with Luftwaffe Chief Hermann Göring (right) and a decorated fighter pilot. Behind Hitler is his chief military aide Wilhelm Keitel, now a Field Marshal. Below: General Heinz Guderian in Russia, full of confidence as well. The new launch date for Barbarossa was Sunday, June 22, 1941. On that day, beginning at 3:15 am, 3.2 million Germans plunged headlong into Russia across an 1800-mile front, taking their foes by surprise. Russian field commanders made frantic calls to headquarters asking for orders, but were told there were no orders. Sleepy-eyed infantrymen scrambled out of their tents to find themselves already surrounded by Germans, with no option but to surrender. Bridges were captured intact while hundreds of Russian planes were destroyed sitting on the ground. At 7 am that morning, over the radio, a proclamation from the Führer to the German people announced, “At this moment a march is taking place that, for its extent, compares with the greatest the world has ever seen. I have decided again today to place the fate and future of the Reich and our people in the hands of our soldiers. May God aid us, especially in this fight.” In attacking Russia, Hitler had indeed stunned the world. But he also made a lot of Germans very nervous. Maria Mauth, a 17-year-old German schoolgirl at the time, recalled her father's reaction: "I will never forget my father saying: 'Right, now we have lost the war!' " But then reports arrived highlighting the easy successes. "In the weekly newsreels we would see glorious pictures of the German Army with all the soldiers singing and waving and cheering. And that was infectious of course...We simply thought it would be similar to what it was like in France or in Poland – everybody was convinced of that, considering the fabulous army we had." Indeed, it was true. Whole armies of hapless Russians were now surrendering as the relentless three-pronged Blitzkrieg blasted its way forward. Soviet Russia had been caught unprepared due to the astounding negligence of the country's dictator, Josef Stalin, who had stubbornly disregarded a flurry of intelligence reports warning that a Nazi invasion was imminent. The result was chaos. Georgy Semenyak, a 20-year-old Russian soldier at the time, remembered: “It was a dismal picture. During the day airplanes continuously dropped bombs on the retreating soldiers…When the order was given for the retreat, there were huge numbers of people heading in every direction…The lieutenants, captains, second-lieutenants took rides on passing vehicles…mostly trucks traveling eastwards…And without commanders, our ability to defend ourselves was so severely weakened that there was really nothing we could do.” Hitler and the Army High Command were now poised to achieve the greatest military victory of all time by trouncing the Russians. At present, three gigantic army groups were proceeding like clockwork toward their objectives. Army Group North, with 20 infantry divisions and six armored divisions, headed for Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) by the Baltic Sea. Army Group Center, the largest, with 33 infantry and 15 armored divisions, continued on its 700-mile-long journey toward Russia’s capital, Moscow. Army Group South, with 33 infantry and eight armored divisions, headed for Kiev, capital of the Ukraine, the breadbasket of Europe with its fertile wheat fields. Along the way, German field commanders employed their already-perfected Blitzkrieg techniques time and time again to pierce Russian defensive lines and surround bewildered Red Army soldiers. June 1941 - Barbarossa

German invasion of the Soviet Union that opened World War II on the Eastern Front, commencing the largest, most bitterly contested, and bloodiest campaign of the war. Adolf Hitler’s objective for Operation BARBAROSSA was simple: he sought to crush the Soviet Union in one swift blow. With the USSR defeated and its vast resources at his disposal, surely Britain would have to sue for peace. So confident was he of victory that he made no effort to coordinate the invasion with his Japanese ally. Hitler predicted a quick victory in a campaign of, at most, three months. German success hinged on the speed of advance of 154 German and satellite divisions deployed in three army groups: Army Group North in East Prussia, under Field Marshal Wilhelm von Leeb; Army Group Center in northern Poland, commanded by Field Marshal Fedor von Bock; and Army Group South in southern Poland and Romania under Field Marshal Karl Gerd von Rundstedt. Army Group North consisted of 3 panzer, 3 motorized, and 24 infantry divisions supported by the Luftflotte 1 and joined by Finnish forces. Farther north, German General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst’s Norway Army would carry out an offensive against Murmansk in order to sever its supply route to Leningrad. Within Army Group Center were 9 panzer, 7 motorized, and 34 infantry divisions, with the Luftflotte 2 in support. Marshal von Rundstedt’s Army Group South consisted of 5 panzer, 3 motorized, and 35 infantry divisions, along with 3 Italian divisions, 2 Romanian armies, and Hungarian and Slovak units. Luftflotte 4 provided air support. Meeting this onslaught were 170 Soviet divisions organized into three “strategic axes” (commanding multiple fronts, the equivalent of army groups)—Northern, Central, and Southern or Ukrainian—that would come to be commanded by Marshals Kliment E. Voroshilov, Semen K. Timoshenko, and Semen M. Budenny, respectively. Voroshilov’s fronts were responsible for the defense of Leningrad, Karelia, and the recently acquired Baltic states. Timoshenko’s fronts protected the approaches to Smolensk and Moscow. And those of Budenny guarded the Ukraine. For the most part, these forces were largely unmechanized and were arrayed in three linear defensive echelons, the first as far as 30 miles from the border and the last as much as 180 miles back.

In World War 2, Hitler and Stalin, two of the most brutal dictators ever, commanded total control and led murderous terror regimes, in which fear of extreme punishment made it almost impossible to criticize or even to offer unfavorable advice, or even to awake the dictator late at night in case of emergency. In such regimes, one man makes all key decisions, and too many lesser decisions, and it's almost impossible to change his mind before or after he makes a major mistake. Here are some examples.

Full-scale development of the LaG-5, as the aircraft was now designated, began, and simultaneously problems arose concerning the initiation of the production process. Especially difficult to build were the first ten aircraft, assembled early in June 1942, which were manufactured in dreadful haste, with numerous errors. While it is normal practice to make parts from drawings, this time, on the contrary, final drawings were sometimes made from the parts. At the same time the tooling was being prepared and the process of producing new components was being mastered. Aircraft Plant No.21 handled the task well. The transition to the modified fighter was effected almost without any reduction in the delivery rate to the air force. Following delivery of the first fully operational LaG-5 on 20th June 1942, the Gorkii workers turned out 37 more by the end of the month. In August the plant surpassed the production rate of all the previous months, 148 LaGG-3s being added to 145 new LaG-5s. Series produced aircraft were considerably inferior to the prototype in speed, being some 24.8 to 31 mph (40 to 50km/h) slower. On the one hand this is understandable, as the LaGG-3 M-82 prototype lacked the radio antenna, bomb carriers and leading edge slats fitted to production aircraft. But there were other contributory causes, particularly insufficiently tight cowlings. Work carried out by Professor V Polinovsky with the workers of the design bureau of Plant No.21 enabled the openings to be found and eliminated. Series built aircraft were sent to war, and the LaG-5's combat performance was proved in the 49th Red Banner Fighter Air Regiment of the 1st Air Army. In the unit's first 17 battles 16 enemy aircraft were shot down at a cost of ten of its own, five pilots being lost. Command believed that the heavy losses occurred because the new aircraft had not been fully mastered and, as a consequence, its operational qualities were not used to full advantage. Pilots noted that, owing to the machine's high weight and insufficient control surface balance, it made more demands upon flying technique than the LaGG-3 and Yak-1. At the same time, however, the LaG-5 had an advantage over fighters with liquid-cooled engines, as its double-row radial protected its pilot from frontal attacks. Aircraft survivability increased noticeably as a consequence. Three fighters returned to their airfield despite pierced inlet nozzles, exhaust pipes and rocker box covers. The involvement of LaG-5s of the 287th Fighter Air Division, commanded by Colonel S Danilov, Hero of the Soviet Union, in the Battle of Stalingrad was a severe test for the aircraft. Fierce fighting took place over the Volga, and the Luftwaffe was stronger than ever before. The division experienced its first combats on 20th August 1942 with 57 LaG-5s, of which two-thirds were combat capable. Four regiments of the division were to have 80 fighters on strength, but a great many deficiencies prevented this. Serious accidents occurred; one fighter crashed during take-off, and two more collided while taxying owing to the pilots' poor view. During the first three flying days the LaGs shot down eight German fighters and three bombers. Seven were lost, including three to 'friendly' anti-aircraft fire. Subsequently, the division pilots were more successful. There were repeated observations of attacks against enemy bombers, of which 57 were destroyed within a month, but the division's own losses were severe. Based on experience gained during combat, the pilots of the 27th Fighter Air Regiment, 287th Fighter Air Division, concluded that their fighters were inferior to Bf109F-4s and, especially, 'G-2s in speed and vertical manoeuvrability. They reported: 'We have to engage only in defensive combat actions. The enemy is superior in altitude and, therefore, has a more favourable position from which to attack.' Hitherto, it has often been stated in Soviet and other historical accounts that the La-5 (the designation assigned to the fighter in early September 1942) had passed its service tests during the Stalingrad battle in splendid fashion. In reality, this advanced fighter still had to overcome some 'growing pains'. This was proved by state tests of the La-5 Series 4 at the NII WS during September and October 1942. At a flying weight of 7,4071b (3,360kg) the aircraft attained a maximum speed at ground level of 316mph (509km/h) at its normal power rating, 332.4mph (535 km/h) at its augmented rating and 360.4mph (580km/h) at the service ceiling of 20,500ft (6,250m) The Soviet-made M-82 family of engines - derived from the US-designed Wright R-1820 Cyclone - had an augmented power rating only at the first supercharger speed). The aircraft climbed to 16,400ft (5,000m) in 6.0 minutes at normal power rating and in 5.7 minutes with augmentation. Its armament was similar to that of the prototype. Horizontal manoeuvrability was slightly improved, but in the vertical plane it was decreased. Many defects in design and manufacture had not been corrected. In combat Soviet pilots flew the La-5 with the canopy open, the cowling side flaps fully open and the tailwheel down, and this reduced its speed by another 18.6 to 24.8mph (30 to 40km/h). As a result, on 25th September 1942 the State Defence Committee issued an edict requiring that the La-5 be lightened, and that its performance and operational characteristics be improved. The industry produced 1,129 La-5s during the second half of 1942, and these saw use during the counter attack by Soviet troops near Stalingrad. Of 289 La-5s in service with fighter aviation, the majority, 180 aircraft, were assigned to the forces of the Supreme Command Headquarters Reserve. The Soviet Command was preparing for a general winter offensive, and was building up reserves to place in support. One of these strong formations became the 2nd Mixed Air Corps under Hero of the Soviet Union Major-General I Yeryomenko, the two fighter divisions of which had five regiments (the 13th, 181st, 239th, 437th and 3rd Guards) equipped with the improved La-5. The new aircraft proved to be 11 to 12.4mph (18 to 20km/h) faster than the fighter which had passed the state tests at the NII WS in September and October 1942. When the 2nd Mixed Air Corps, with more than 300 first class combat aircraft, was used to reinforce the 8th Air Army, the latter had only 160 serviceable aircraft. The 2nd Mixed Air Corps, reliably protecting and supporting the counter offensive by troops along the lines of advance, flew over 8,000 missions and shot down 353 enemy aircraft from 19th November 1942 to 2nd February 1943. Progress made in combat activities by the Air Corps aviators in co-operation with joint forces during offensive operations on the Stalingrad and Southern fronts were noted by the ground forces Command. General Rodion Malinovsky, Commander of the 2nd Guards Army (later Defence Minister), wrote: 'The active warfare of the fighter units of the 2nd Mixed Air Corps [of which 80% of its aircraft were La-5s], by covering and supporting combat formations of Army troops, actually helped to protect the army from enemy air attacks. Pilots displayed courage, heroism and valour in the battlefield. With appearance of the Air Corps fighters the hostile aircraft avoided battle.

These men are Russian officers in the ROA, the Russian Liberation Army (In Russian: Russkaya Osvoboditelnaya Armiya). They are a part of captured Russian soldiers who joined the Germans and their Allies in the struggle against Bolshevism. The officer second from the left is General Vlasov. The ROA consisted of two divisions under the command of General Vlasov and its popular name was Vlasov's army. By 1944 defeat stared Germany in the face. Goebbels's propaganda machine did its best to counter the deterioration of morale, especially emphasizing the bleak prospects with which the "unconditional surrender" slogan confronted the German people. On July 20 a few army officers and government officials attempted to kill Hitler and overthrow the Nazi regime, but the plot miscarried and merely resulted in the liquidation of the chief non-Nazis anywhere near the summit of power. Opportunely for Goebbels came Allied publication of lists of "war criminals," the mass proscription of the German General Staff, and the approval of the "Morgenthau Plan," which envisaged the destruction of German industry and the conversion of all Germany into "a country primarily agricultural and pastoral in character," at the second Quebec conference in September 1944. Goebbels declared, "It hardly matters whether the Bolshevists want to destroy the Reich in one fashion and the Anglo-Saxons propose to do it in another." Doubtless the Morgenthau Plan did much to confuse those Germans who might be thinking of surrendering to the West while holding out against Stalin,, and thus Stalin could only profit by its dissemination by the U.S. and Britain. At virtually the same moment that the Allies were endorsing the Morgenthau Plan at Quebec, the Nazi regime turned in desperation to a weapon which, if used earlier, might indeed have had great effect on the outcome of the war, but what the Nazis did with it in 1944 was too little and much too late. General Vlasov, who had been captured two years earlier, was to be transformed from a pawn of Nazi propaganda into the leader of a real Soviet anti-Stalinite army and government. Vlasov, who was born in 1900, the son of a peasant family of Nizhnii Novgorod, had risen in Red Army ranks. A Party member since 1930, he had been Soviet military adviser to Chiang Kai-shek in 1938-1939, decorated in 1940, and in the autumn of 1941 one of the chief army commanders in the defense of Moscow. Apparently he possessed great personal magnetism, integrity, and ability. Not at all the opportunist and Nazi hireling he was accused of being, Vlasov "stressed his nationalism and strove to preserve the independence of the Movement," writes the most recent Investigator. Of the most influential men who joined his cause, probably the ablest was the brilliant but mysterious Milenty Zykov, who said he had been on the staff of Izvestiia under Bukharin and for a time had been exiled by Stalin. When captured he claimed to be serving as a battalion commissar, but it was suspected that he was much more. By the end of 1942 Captain Wilfried Strik-Strikfeldt of the German army propaganda section was planning to establish a Russian National Committee led by Vlasov at Smolensk. The plan was vetoed from above, but in December the formation of the committee was proclaimed on German soil Instead. Vlasov published a statement of his aims, and he was allowed to tour occupied Soviet areas, meeting a considerable popular response. In April 1943 an anti-Bolshevik conference of Soviet prisoners opposed to Stalin's regime was held in Brest-Litovsk. After Vlasov declared that if successful he would grant Ukraine and the Caucasus self-determination, Rosenberg was persuaded to support the committee. However, in June 1943 Hitler ordered that Vlasov was to be kept out of the occupation zone, and that the movement was to be confined to propaganda—that is, promises which Hitler could ignore later—across the lines to Soviet-held territory. During 1943 Vlasov's circle, under the protection of Strik-Strikfeldt's section at Dabendorf just outside Berlin, was allowed to carry on remarkably free discussions about a future non-Communist government for Russia and to publish two newspapers in Russian, one for Soviet war prisoners and another for the Osttruppen. The political center of gravity at Dabendorf fluctuated between the more socialist-inclined entourage of Zykov and the more authoritarian-minded group close to the emigre anti-Soviet organization, N.T.S. (Natsionalno-Trudovoi Soiuz or National Tollers' Union). Of course political arguments among Soviet emigres were nothing new; what was new was the hope of imminent action, utilizing the five million Soviet nationals in Germany, to overthrow Stalin—either with Hitler's support or, if he should fall, perhaps in conjunction with the Western Allies. Despite arguments, a fair degree of harmony was maintained among the Russians at Dabendorf. Especially noteworthy was the extent to which Vlasov and his followers succeeded in preventing themselves from being compromised by Nazi Ideology and in maintaining the integrity of their own effort to win Russian freedom. Until 1944, however, the Vlasov circle was confined to discussion and publication. Although the phrase, "Russian Liberation Army," and Its Russian abbreviation, ROA (for Russkaia Osvoboditel'naia Armiia), were much used in propaganda— with Hitler's approval—there was in fact no such army. "ROA" was only a shoulder patch which the Osttruppen, scattered in small units throughout the Nazi army, were permitted to wear. In the summer of 1944 the ablest Intellectual of the Vlasov group, Zykov, was abducted and almost certainly murdered forthwith by the SS. Nevertheless it was Himmler, chief of the SS, who not long afterward achieved the reversal of Nazi policy toward Vlasov. In a meeting with Vlasov in mid-September 1944, Himmler agreed to the formation of a Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (Komitet Osvobozhdeniia Narodov Rossii or K.O.N.R.), which would have the potentiality of a government, and an actual army. It appears that Hitler consented to Himmler's new policy chiefly because his suspicion of other Nazi officials who opposed it was by 1944 greater than his fear of arming enemy nationals—a fear which, it must be said, was justified from the Nazi standpoint. The concrete results of Himmler's decision were meager, largely because the Russians could not, amid the disintegration which overtook the Nazi system during the last months of the war, obtain the material aid they needed to implement their plans. However, in November 1944 in Prague the K.O.N.R. was officially established at a meeting which issued the so-called "Prague Manifesto." This document, declaring that the irruption of the Red armies into Eastern Europe revealed more clearly than ever the Soviet "aim to strengthen still more the mastery of Stalin's tyranny over the peoples of the USSR, and to establish it all over the world," stated the goals of the K.O.N.R. to be the overthrow of the Communist regime and the "creation of a new free People's political system without Bolsheviks and exploiters." It proclaimed recognition of the "equality of all peoples of Russia" and their right of self-determination as well as the intention of ending forced labor and the collective farms and of achieving real civil liberties and social justice. If such a document had been widely disseminated two or three years earlier and given some substance in Nazi occupation policy, the results might have been important or even decisive; coming in 1944, it had no observable effect on the Soviet peoples. The Prague meeting did stimulate certain Nazi officials to make efforts to put the minorities into the picture with political committees and armies. A year earlier the Nazis had finally organized a Ukrainian SS division which bore the name "Galicia," but although it fought hard and well at the battle of Brody, on the Rovno-Lvov road, in July 1944, when it was finally overrun there, it dispersed to join Ukrainian partisan forces behind Red lines. In October an SS official, Dr. Fritz Arlt, attempted to secure the consent of the Ukrainian nationalist leaders to the formation of a Ukrainian national committee. To avoid being overshadowed by Vlasov, Bandera and Melnyk agreed to the setting up of such a committee, nominally headed by General Paul Shandruk. Melnyk protested the Prague Manifesto, but many Ukrainians nevertheless joined the Vlasov movement, along with representatives of other minorities. In January 1945 the formation of the Armed Forces of the K.O.N.R. was announced; however, only two divisions were actually activated and mobilized. The First Division, under the command of a Ukrainian, General S. K. Buniachenko, was committed in April on the front near Frankfurt on the Oder, but the unit refused to fight under existing circumstances, and amid the Nazi military collapse moved south toward Czechoslovakia. At the call of the Czech resistance leaders in Prague, the division moved into the city and on May 7, with Czech aid, captured it from the Nazis. However, in the Europe of the spring of 1945 there was no place for an anti-Soviet Russian army. The generals, including Vlasov, were turned over to the Soviet command by American and British forces, with or without authorization to do so. In February 1946 the remainder of the army was handed over by U.S. authorities without warning to Soviet repatriation officers at Plattling, Bavaria. In August Pravda announced the execution of Vlasov and his fellow officers, describing them as "agents of German intelligence" and failing to inform the Russian people that they had organized a movement to overthrow Stalin. By mid-July 1941, all that remained was for the Russians to give up and accept their fate under Hitler, just like Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland, France, Yugoslavia, and Greece. But the Russians kept fighting. October 1941. German infantrymen plunge ever deeper into Russia. Below: Hitler at the map table with Army Commander-in-Chief Brauchitsch and others, including Friedrich Paulus (2nd from left). Despite staggering losses of men and equipment, pockets of fanatical resistance now emerged, unlike anything the Germans had encountered thus far in the war. And there were more surprises for the Germans. They had grossly underestimated the total fighting strength of the Red Army. Instead of 200 divisions, the Russians could field 400 divisions when fully mobilized. This meant there were three million additional Russians available to fight. Another emerging factor was the vastness of Russia itself. It was one thing to ponder a map, something else to traverse the boundless countryside, as Field Marshal Manstein remembered: "Everyone was captivated at one time or other by the endlessness of the landscape, through which it was possible to drive for hours on end – often guided by the compass – without encountering the least rise in the ground or setting eyes on a single human being or habitation. The distant horizon seemed like some mountain ridge behind which a paradise might beckon, but it only stretched on and on." The vastness created logistical problems including worn out foot soldiers and dangerously overstretched supply lines. It also taxed the ability of the Luftwaffe to provide close cover for advancing ground troops, a vital ingredient in the Blitzkrieg formula. On top of this, Russian resistance began to stiffen all over as the soldiers and people rallied behind Stalin in the defense of their Motherland. Stalin, at first overwhelmed by the magnitude of Barbarossa, had regained his bearings and publicly appealed for a "Great Patriotic War" against the Nazi invaders. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, he enacted ruthless measures, executing his top commander in the west and various field commanders who had been too eager to retreat. Under Stalin's tight-fisted grip, the chaos and panic that had initially enveloped the Russian officer corps gradually subsided. Red Army commanders took heed from Stalin, instilling his 'fight to the death' mentality in their frontline soldiers. They set up new defensive positions, not to be yielded until every last soldier was killed. They also began their first-ever counter-attacks against the advancing Germans. As a result, with each passing day the Germans began to lose momentum. They could no longer easily blow through the Russian defenses and had to be wary of counter-strikes. All the while, German foot soldiers were becoming increasingly fatigued. By August of 1941, it had become apparent to the Army High Command there would be no speedy victory. “The whole situation makes it increasingly plain that we have underestimated the Russian colossus,” General Franz Halder, Chief of the General Staff, had to admit. Therefore the question now arose – what to do – follow the original battle plan for Barbarossa or make changes to adapt? Army Group Center was presently about 200 miles from Moscow, poised for a massive assault. However, the original plan called for Army Groups North and South to stage the main attacks in Russia, with Army Group Center playing a supporting role until their tasks were completed, after which Moscow would be taken. A majority of Hitler’s senior generals now implored him to scrap Barbarossa in favor of an all-out attack on Moscow. If the Russian capital fell, they argued, it would devastate Russian morale and knock out the country’s chief transportation hub. Russia’s days would surely be numbered. The decision rested solely with the Supreme Commander. In what was perhaps his single biggest decision of World War II, Hitler passed up the chance to attack Moscow during the summer of 1941. Instead, he clung to the original plan to crush Leningrad in the north and simultaneously seize the Ukraine in the south. This, Hitler lectured his generals, would be far more devastating to the Russians than the fall of Moscow. A successful attack in the north would wreck the city named after one of the founders of Soviet Russia, Vladimir Lenin. Attacking the south would destroy the Russian armies protecting the region and place vital agricultural and industrial areas in German hands. Though they remained unconvinced, the generals dutifully halted the advance on Moscow and repositioned troops and tanks away from Army Group Center to aid Army Groups North and South. By late September, bolstered by the additional Panzer tanks, Army Group South successfully captured the city of Kiev in the Ukraine, taking 650,000 Russian prisoners. As Army Group North approached Leningrad, a beautiful old city with palaces that once belonged to the Czars, Hitler ordered the place flattened via massive aerial and artillery bombardments. Concerning the five million trapped inhabitants, he told his generals, “The problem of the survival of the population and of supplying it with food is one which cannot and should not be solved by us.” Now, with Leningrad surrounded and the Ukraine almost taken, the generals implored Hitler to let them take Moscow before the onset of winter. This time Hitler consented, but only partly. He would allow an attack on Moscow, provided that Army Group North also completed the capture of Leningrad, while Army Group South advanced deeper into southern Russia toward Stalingrad, the city on the Volga River named after the Soviet dictator. This meant German forces in Russia would be attacking simultaneously on three major fronts over two thousand miles long, stretching their manpower and resources to the absolute limit. Realizing the danger, the generals pleaded once more for permission to focus on Moscow alone and strike the city with overwhelming force. But Hitler said no. In the meantime, German troops still holding outside Moscow had remained idle for nearly two months, waiting for orders to advance. When the push finally began on October 2, 1941, a noticeable chill already hung in the morning air, and in a few places, snowflakes wafted from the sky. The notorious Russian winter was just around the corner. At first it appeared Moscow might be another easy success. Two Russian army groups defending the main approach were quickly encircled and broken up by motorized Germans who took 660,000 prisoners. Confident the war in Russia was just about won, Hitler took a leap by announcing victory to the German people: “I declare today, and I declare it without any reservation, that the enemy in the East has been struck down and will never rise again…Behind our troops already lies a territory twice the size of the German Reich when I came to power in 1933.” By mid-October, forward German units had advanced to within 40 miles of Moscow. Only 90,000 Russian soldiers stood between the German armies and the Soviet capital. The entire government, including Stalin himself, prepared to evacuate. But then the weather turned. Russian Winter. Near Moscow, a wounded German is rescued. Below: A Panzer III tank stuck in the snow and cold as the whole offensive stalls. It began with weeks of unending autumn rain, creating battlefields of deep, sticky mud that immobilized anything on wheels and robbed German armored units of their tactical advantage. The non-stop rain drenched foot soldiers, soaking them to the bone in mud up to their knees. And things only got worse. In November, autumn rains abruptly gave way to snow squalls with frigid winds and sub-zero temperatures, causing frostbite and other cold-related sickness. The German Army had counted on a quick summertime victory in Russia and had therefore neglected to prepare for the brutal winter warfare it now faced. German medical officer Heinrich Haape recalled: “The cold relentlessly crept into our bodies, our blood, our brains. Even the sun seemed to radiate a steely cold and at night the blood red skies above the burning villages merely hinted a mockery of warmth.” Heavy boots, overcoats, blankets and thick socks were desperately needed but were unavailable. As a result, thousands of frostbitten soldiers dropped out of their frontline units. Some divisions fell to fifty-percent of their fighting strength. Food supplies also ran low and the troops became malnourished. Mechanical failures worsened as tank and truck engines cracked from the cold while iced-up artillery and machine-guns jammed. The once-mighty German military machine had now ground to a halt in Russia. Frontline Russians noticed the change. A Soviet commander in the 19th Rifle Brigade recalled: "I remember very well the Germans in July 1941. They were confident, strong tall guys. They marched ahead with their sleeves rolled up and carrying their machine-guns. But later on they became miserable, crooked, snotty guys wrapped in woolen kerchiefs stolen from old women in villages...Of course, they were still firing and defending themselves, but they weren't the Germans we knew earlier in 1941." Ignoring the plight of his frontline soldiers, Hitler insisted that Moscow could still be taken and ordered all available troops in the region to make one final thrust for victory. Beginning on December 1, 1941, German tank formations attacked from the north and south of the city while infantrymen moved in from the east. But the Russians were ready and waiting. The weather delays had given them time to bring in massive reinforcements, including 30 Siberian divisions specially trained for winter warfare. Wherever the Germans struck they encountered fierce resistance and faltered. They were also stricken by temperatures that plunged to 40 degrees below zero at night. Hitler had pushed his troops beyond human endurance and now they paid a terrible price. On Saturday, December 6th, a hundred Russian divisions under the command of the Red Army's new leader, General Georgi Zhukov, counter-attacked the Germans all along the 200-mile front around Moscow. For the first time in the war, the Germans experienced Blitzkrieg in reverse, as overwhelming numbers of Russian tanks, planes and artillery tore them apart. The impact was devastating. By mid-December, German forces around Moscow, battered, cold and tremendously fatigued, were in full retreat and facing the possibility of being routed by the Russians. Just six months earlier, the Germans had been poised to achieve the greatest victory of all time and change world history. Instead, they had succumbed to the greatest-ever comeback by their Russian foes. By now a quarter of all German troops in Russia, some 750,000 men, were either dead, wounded, missing or ill. Reacting to the catastrophe he had caused, Hitler blamed the Wehrmacht's leadership, dismissing dozens of field commanders and senior generals, including Walther von Brauchitsch, Commander-in-Chief of the Army. Hitler then took that rank for himself, assuming personal day-to-day operational command of the Army, and promptly ordered all surviving troops in Russia to halt in their tracks and retreat not one step further, which they did. As a result, the Eastern Front gradually stabilized. In the bloodied fields of snow around Moscow, Adolf Hitler had suffered a breathtaking defeat. The German Army would never be the same. The illusion of invincibility that had caused the world to shudder in the face of Nazi Germany had vanished forever – replaced now by a sliver of hope. But for the populations of Eastern Europe and occupied Russia, there was much suffering yet to be endured. In cities and villages behind the front lines, Hitler's war of annihilation was fully underway, comprising the most savage episode in human history.

Because of his experiences in Vienna, World War One, the Münich putsch and in prison, Adolf Hitler dreamed of building a vast German Empire sprawling across Central and Eastern Europe. Lebensraum could only be obtained and sustained by waging a war of conquest against the Soviet Union: German security demanded it and Hitler's racial ideology required it. War, then, was essential. It was essential to Hitler the man as well as essential to Hitler's dream of a new Germany. In the end, most historians have reached the consensus that World War Two was Hitler's war (for more on Hitler, see Lecture 9 and Lecture 10). Unfortunately, although most western statesmen had sufficient warning that Hitler was a threat to a general European peace, they failed to rally their people and take a stand until it was too late. Following 1933 -- the year when Hitler consolidated his power as Chancellor through the Enabling Act -- Hitler implemented his foreign policy objectives. These objectives clearly violated the provisions of the Versailles Treaty. Hitler's foreign policy aims accorded with the goals of Germany's traditional rulers in that the aim was to make Germany the most powerful state in all of Europe. For example, during World War One, German generals tried to conquer extensive regions in Eastern Europe. And with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918) between Germany and Russia, Germany took Poland, the Ukraine and the Baltic States from Russia. However, where Hitler departed from this traditional scenario was his obsession with racial supremacy. His desire to annihilate whole races of inferior peoples marked a break from the outlook of the old order. This old order never contemplated the restriction of the civil rights of the Jews. They wanted to Germanize German Poles, not enslave them. But Hitler was an opportunist -- he was a man possessed and driven by a fanaticism that saw his destiny as identical to Germany's. The propaganda machine that Hitler adopted, however, was perhaps the most important device at his disposal. With it he was able to successfully undermine his opponent's will to resist. And propaganda, after winning the minds of the German people, now became a most crucial instrument of German foreign policy as a whole. There were upwards of 27 million German people living outside the borders of the Reich. To force those 27 million into support for Hitler, the Nazis utilized their propaganda machine. For example, they made every effort to export anti-Semitism internationally, thus feeding off prejudices of other nations. Hitler also began to promote himself as Europe's best defense against Stalin, the Bolsheviks and the Soviet Union (on Stalin see Lecture 10). In fact, the Nazi anti-Bolshevik propaganda convinced thousands of Europeans that Hitler was also Europe's best defense against all Communists.

Hitler was a shrewd statesman. He anticipated, for instance, that the British and French would back down the moment they were faced with his direct and willful violations of Versailles. He knew that any threat of war would drive the Anglo-French into a defensive posture. The reason for this should be pretty clear -- Britain and France would have done anything to avoid another conflict and this defensive position managed to win a vote of confidence from public opinion. The British believed that Germany had been treated too harshly by the provisions of Versailles and because of this, they were willing to make concessions to the Germans. The French, with the largest army on the Continent, refused to contemplate an offensive war, as was their position in World War One, and decided instead to protect their borders at all costs. The United States, meanwhile, stood aloof from any European conflict because they had their own problems to deal with, namely, the Great Depression. To top it all off, the British and French no longer trusted Russia, so the hopes of establishing an alliance along the lines which developed during the Great War was just not possible. So the British introduced their policy of appeasement. They hoped that by making concessions to Hitler, war would be avoided. They also held on to the illusion that Hitler was, once again, Europe's best defense against Soviet Russia. The British appeasers certainly missed the boat -- even with Mein Kampf in their hands, they failed to understand Hitler's foreign policy aims. Hitler could be reasoned with, they argued. Meanwhile, Germany grew stronger and the German people began to look to Hitler as their messiah. Hitler needed a strong army to realize his war aims. According to the provisions of the Versailles Treaty, the Germany army was to be limited to 100,000 soldiers. The size of the navy was limited as well. Germany was also forbidden to produce military aircraft, tanks and heavy artillery. The General Staff was dissolved. These were harsh provisions. How did Germany get by these conditions? Well, actually it was quite easy. In March 1935, Hitler declared that Germany was no longer bound by the provisions of the Versailles Treaty. He began conscription and built up the air force. France protested, weakly, and Britain negotiated a naval agreement with the Germans. One year later, on March 7, 1936, Hitler marched his troops into the Rhineland, a clear violation of Versailles. His generals cautioned Hitler that such a move would provoke an attack. Again, Hitler judged the Anglo-French response correctly. The British and French took no action. The British sat back. The French saw the remilitarization of the Rhineland as a grave threat to their security. With 22,000 German soldiers standing along the French border, why didn't the French act? The first reason was that France would not act alone and Britain offered no help at this point. Second, the French over-estimated German forces who marched into the Rhineland. Again, their posture was decidedly defensive. And lastly, French public opinion was strongly opposed to any confrontation with Hitler. Meanwhile, European fascism was winning another war in Spain between 1936 and 1937. Mussolini and Hitler both supported Franco's right-wing dictatorship and as to be expected, the French refused to intervene. The Spanish Civil War was decisive for Hitler for it was here that he was able to test new weapons and new aircraft which would eventually make their appearance when World War Two finally broke out in 1939. And then in 1938, Hitler ordered his troops to march into Austria, which then became a province of Germany. The Austrians celebrated by ringing church bells, waving swastikas and attacking Jews. The Anschluss was yet another violation of Versailles. Why had so many people missed the boat? In Mein Kampf, Hitler had made it quite clear that Austria must be annexed to Germany, Did anyone listen? Did anyone make any effort to prevent Anschluss? No! Britain and France both informed the Chancellor of Austria that they would not help if invaded by Germany. Once again, non-intervention paved the way for Hitler's foreign policy aims.

The period of six months following the fall of Poland has been called "the phony war." Fighting was limited to minor skirmishes along the French and German borders. But in April 1940, Hitler struck at Denmark and Norway. Hitler needed to establish naval bases in these countries from which his submarines could attack England. Denmark surrendered in only one day and Norway soon followed. The following month, Hitler attacked Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg. Surrenders followed quickly. Meanwhile, French troops rushed to Belgium to prevent a German breakthrough. The German forces converged on the French port of Dunkirk, the last point of escape for the Allies. But Hitler called off his tanks and planned to use airstrikes to annihilate the Allies. As it turned out, fog and rain prevented Hitler from using the full force of his airplanes. 340,000 British and French forces were ferried across the English Channel to England while Germany bombed the beaches. By late Spring 1940, there was every indication that France was about to fall to the Nazis. Numerous French divisions were cut off and in retreat. Millions of French refugees were making their way south and on June 10, 1940, Mussolini declared war on France. The French government sent out an appeal for armistice and so on June 22, 1940, French and German officials met in a railway car and signed the agreement. In a odd twist of fate, it was the same railway car used to sign the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles back in 1918. With France fallen, Hitler assumed that Britain would make peace. The British rejected any overtures on the part of the Germans and so in August 1940, Hitler ordered his Luftwaffe to conduct massive airstrikes against Britain and the Battle of Britain had begun. The battle raged for almost five months. On September 15, the British RAF shot down sixty German aircraft and Hitler was forced to postpone his invasion of Britain. The Germans, however, continued their night time attacks on English cities and towns but British morale never broke during the Blitz. By the end of 1941, Hitler had also invaded Russia but Russia would not yield. By early 1942, Nazi Germany ruled virtually all of Europe. Territories were annexed, some were under German military authority while still others, such as France, collaborated with the Nazis. It was over this vast empire that Hitler intended to superimpose a New Order. The Germans expropriated and exploited every country which they conquered. They took gold, art, machinery and food supplies back to Germany. Some foreign factories were confiscated -- others produced what the Germans demanded. The bottom line is quite simple -- the Germans took whatever it was they wanted. Seven million people from all over occupied Europe were enslaved and transported to Germany where they lived and worked in forced labor camps. The Nazis rules by terror and fear. The New Order meant torture, prison, firing squads and concentration camps. For example, in Poland, priests and intellectuals were jailed and killed and most schools and churches were ordered closed. In Russia, political officials were immediately executed and prisoners of war were herded into camps and worked to death. Germany ended up taking 5.5 million Russian POWs, 3.5 million of which were killed or died in captivity.

To expedite the Final Solution, the Nazis began to use concentration camps. These camps were already in existence for the use of political prisoners. Jews from all over Europe were rounded up under the notion that they were about to be resettled. Although the Jews knew something about plans for their eventual extermination, they just could not believe that any 20th century nation would resort to such a crime against humanity. Of course, the Holocaust was a reality. Cattle cars full of Jews and other inferior races traveled days without food or water. When the doors opened, they found themselves in the unreal world of the concentration camp. SS doctors then inspected the "freight." Rudolf Hoess (1900-1947), commandant at Auschwitz described the procedure in the following way:

Auschwitz was more than a death factory. It also provided I. G. Farben with slave laborers, both Jew and non-Jew. Workers worked at a pace at which even the healthiest of workers would have found intolerable. And because Germany now had somewhat of an unlimited labor supply, working prisoners as fast as possible would solve two problems at the same time: increased production and the extermination of inmates. Auschwitz also allowed the SS, the elite members of the master race, to shape themselves according to Nazi ideology. The SS, for instance, amused themselves with pregnant women, women who were beaten with clubs, attacked by dogs, dragged by the hair and then thrown into the crematory, still alive. The SS systematically overworked, starved and beat their inmates. They made them live in filth and sleep in over-crowded rooms. The purpose of such inhuman behavior was to rob the individual of any shred of human dignity. In this way, the SS and the Nazis could demonstrate -- to themselves, of course -- that the Jew was clearly an inferior race of people. After hours or weeks, exhausted, starving, diseased and beaten, these men and women were sent to the gas chamber.

Across occupied territories of the Third Reich there were Nazi collaborators who welcomed the fall of democracy and who still saw Hitler as the best defense against communism. But each country also produced a resistance movement that grew stronger as Nazi atrocities increased. The resistance movement rescued downed pilots, radioed military movements to London, and sabotaged German railway depots. The Danish underground managed to smuggle 8000 Jews into Sweden while the Polish resistance, estimated to number 300,000, reported on German positions and interfered with the movement of supplies. Russian partisans sabotaged railways, destroyed trucks and killed hundreds of Germans in ambush. The Yugoslav resistance army, led by Marshall Tito, was a disciplined fighting force which ultimately liberated the country from the Germans. European Jews were specifically active in the French resistance movement. But in eastern Europe, the Jewish resisters received little or no support and were usually denounced to the Nazis. The Germans responded harshly to the Jewish resistance. For example, 200 Jews were killed for every one Nazi. However, in the Spring of 1943, the surviving Jews of the Warsaw ghetto managed to fight the Germans for several weeks. Also, in 1943, and after the Allies had landed in Italy, Italian resisters managed to liberate the country from the fascists and German occupation. And on July 20, 1944, Colonel Stauffenberg planted a bomb under Hitler's table at staff conference meeting -- the bomb exploded but Hitler escaped serious injury. The Nazis responded by torturing and executing 5000 suspected anti-Nazis.

The legacy of World War Two was dramatic. 50 million lost their lives, 20 million Russians alone. The war also meant a vast number of people left Europe for either England or the United States in an exodus which has come to be known as the Great Sea Change. Hundreds of cities were destroyed, some of them centuries-old. Only 5% of Berlin remained intact, 70% of Dresden, Hamburg, Munich and Frankfurt were destroyed. The war also revealed the existence of two superpowers -- the United States and the Soviet Union, countries which would determine the fate of Europe and the world for the next four decades. The world now had to atomic bomb. The world also had its Satan: Hitler. Vast imperialist empires were destroyed and then there was the Holocaust. In the intellectual realm and in the world of art, the European war created a Second Lost Generation with its own philosophy: existentialism. The final chapter in the destruction of Hitler's Third Reich began on April 16, 1945 when Stalin unleashed the brutal power of 20 armies, 6,300 tanks and 8,500 aircraft with the objective of crushing German resistance and capturing Berlin. By prior agreement, the Allied armies (positioned approximately 60 miles to the west) halted

Devastation in Berlin their advance on the city in order to give the Soviets a free hand. The depleted German forces put up a stiff defense, initially repelling the attacking Russians, but ultimately succumbing to overwhelming force. By April 24 the Soviet army surrounded the city slowly tightening its stranglehold on the remaining Nazi defenders. Fighting street-to-street and house-to-house, Russian troops blasted their way towards Hitler's chancellery in the city's center. Inside his underground bunker Hitler lived in a world of fantasy as his "Thousand Year Reich" crumbled above him. In his final hours the Fuehrer married his long-time mistress and then joined her in suicide. The Third Reich was dead. Beginning of the End Dorothea von Schwanenfluegel was a twenty-nine-year-old wife and mother living in Berlin. She and her young daughter along with friends and neighbors huddled within their apartment building as the end neared. The city was already in ruins from Allied air raids, food was scarce, the situation desperate - the only hope that the Allies would arrive before the Russians. We join Dorothea's account as the Russians begin the final push to victory: "Friday, April 20, was Hitler's fifty-sixth birthday, and the Soviets sent him a birthday present in the form of an artillery barrage right into the heart of the city, while the Western Allies joined in with a massive air raid. The radio announced that Hitler had come out of his safe bomb-proof bunker to talk with the fourteen to sixteen year old boys who had 'volunteered' for the 'honor' to be accepted into the SS and to die for their Fuhrer in the defense of Berlin. What a cruel lie! These boys did not volunteer, but had no choice, because boys who were found hiding were hanged as traitors by the SS as a warning that, 'he who was not brave enough to fight had to die.' When trees were not available, people were strung up on lamp posts. They were hanging everywhere, military and civilian, men and women, ordinary citizens who had been executed by a small group of fanatics. It appeared that the Nazis did not want the people to survive because a lost war, by their rationale, was obviously the fault of all of us. We had not sacrificed enough and therefore, we had forfeited our right to live, as only the government was without guilt. The Volkssturm was called up again, and this time, all boys age thirteen and up, had to report as our army was reduced now to little more than children filling the ranks as soldiers." Encounter with a Young Soldier "In honor of Hitler's birthday, we received an eight-day ration allowance, plus one tiny can of vegetables, a few ounces of sugar and a half-ounce of real coffee. No one could afford to miss rations of this type and we stood in long lines at the

Hitler's last public appearance grocery store patiently waiting to receive them. While standing there, we noticed a sad looking young boy across the street standing behind some bushes in a self-dug shallow trench. I went over to him and found a mere child in a uniform many sizes too large for him, with an anti-tank grenade lying beside him. Tears were running down his face, and he was obviously very frightened of everyone. I very softly asked him what he was doing there. He lost his distrust and told me that he had been ordered to lie in wait here, and when a Soviet tank approached he was to run under it and explode the grenade. I asked how that would work, but he didn't know. In fact, this frail child didn't even look capable of carrying such a grenade. It looked to me like a useless suicide assignment because the Soviets would shoot him on sight before he ever reached the tank. By now, he was sobbing and muttering something, probably calling for his mother in despair, and there was nothing that I could do to help him. He was a picture of distress, created by our inhuman government. If I encouraged him to run away, he would be caught and hung by the SS, and if I gave him refuge in my home, everyone in the house would be shot by the SS. So, all we could do was to give him something to eat and drink from our rations. When I looked for him early next morning he was gone and so was the grenade. Hopefully, his mother found him and would keep him in hiding during these last days of a lost war." The Russians Arrive "The Soviets battled the German soldiers and drafted civilians street by street until we could hear explosions and rifle fire right in our immediate vicinity. As the noise got closer, we could even hear the horrible guttural screaming of the Soviet soldiers which sounded to us like enraged animals. Shots shattered our windows and shells exploded in our garden, and suddenly the Soviets were on our street. Shaken by the battle around us and numb with fear, we watched from behind the small cellar windows facing the street as the tanks and an endless convoy of troops rolled by... It was a terrifying sight as they sat high upon their tanks with their rifles cocked, aiming at houses as they passed. The screaming, gun-wielding women were the worst. Half of the troops had only rags and tatters around their feet while others wore SS boots that had been looted from a conquered SS barrack in Lichterfelde. Several fleeing people had told us earlier that they kept watching different boots pass by their cellar windows. At night, the Germans in our army boots recaptured the street that the

A Soviet soldier raises the Soviets in the SS boots had taken during the day. The boots and the voices told them who was who. Now we saw them with our own eyes, and they belonged to the wild cohorts of the advancing Soviet troops. Facing reality was ten times worse than just hearing about it. Throughout the night, we huddled together in mortal fear, not knowing what the morning might bring. Nevertheless, we noiselessly did sneak upstairs to double check that our heavy wooden window shutters were still intact and that all outside doors were barricaded. But as I peaked out, what did I see! The porter couple in the apartment house next to ours was standing in their front yard waving to the Soviets. So our suspicion that they were Communists had been right all along, but they must have been out of their minds to openly proclaim their brotherhood like that. As could be expected, that night a horde of Soviet soldiers returned and stormed into their apartment house. Then we heard what sounded like a terrible orgy with women screaming for help, many shrieking at the same time. The racket gave me goosebumps. Some of the Soviets trampled through our garden and banged their rifle butts on our doors in an attempt to break in. Thank goodness our sturdy wooden doors withstood their efforts. Gripped in fear, we sat in stunned silence, hoping to give the impression that this was a vacant house, but hopelessly delivered into the clutches of the long-feared Red Army. Our nerves were in shreds." Looting "The next morning, we women proceeded to make ourselves look as unattractive as possible to the Soviets by smearing our faces with coal dust and covering our heads with old rags, our make-up for the Ivan. We huddled together in the central part of the basement, shaking with fear, while some peeked through the low basement windows to see what was happening on the Soviet-controlled street. We felt paralyzed by the sight of these husky Mongolians, looking wild and frightening. At the ruin across the street from us the first Soviet orders were posted, including a curfew. Suddenly there was a shattering noise outside. Horrified, we watched the Soviets demolish the corner grocery store and throw its contents, shelving and furniture out into the street. Urgently needed bags of flour, sugar and rice were split open and spilled their contents on the bare pavement, while Soviet soldiers stood guard with their rifles so that no one would dare to pick up any of the urgently needed food. This was just unbelievable. At night, a few desperate people tried to salvage some of the spilled food from the gutter. Hunger now became a major concern because our ration cards were worthless with no hope of any supplies. Shortly thereafter, there was another commotion outside, even worse than before, and we rushed to our lookout to see that the Soviets had broken into the bank and were looting it. They came out yelling gleefully with their hands full of German bank notes and jewelry from safe deposit boxes that had been pried open. Thank God we had withdrawn money already and had it at home." Surrender

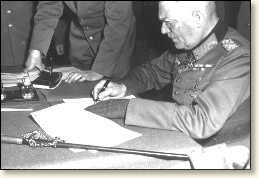

Field Marshall Keitel signs the surender terms "The next day, General Wilding, the commander of the German troops in Berlin, finally surrendered the entire city to the Soviet army. There was no radio or newspaper, so vans with loudspeakers drove through the streets ordering us to cease all resistance. Suddenly, the shooting and bombing stopped and the unreal silence meant that one ordeal was over for us and another was about to begin. Our nightmare had become a reality. The entire three hundred square miles of what was left of Berlin were now completely under control of the Red Army. The last days of savage house to house fighting and street battles had been a human slaughter, with no prisoners being taken on either side. These final days were hell. Our last remaining and exhausted troops, primarily children and old men, stumbled into imprisonment. We were a city in ruins; almost no house remained intact." The Rise and Fall of the first German Democracy Summary: Weimar democracy, which arose from defeat and which replaced a semi-authoritarian imperialist regime, never had very wide support. Despite opposition from right and left the Weimar Republic survived to years of greater internal peace from the mid- 1920s, when the fundamental political problems were masked, until exposure by the economic and political crises of 1929 Hitler's appointment as German Chancellor in 1933 was arguably the most important event of the twentieth century. Within six years it led to the vast destruction and profound, world-wide changes of the Second World War. It is therefore crucial for historians to explain how so violent, barbaric and destructive a movement came to control an advanced and civilised country. The most direct causes for the collapse of the first German democracy must be sought in the years between the end of the First World War and the establishment of the Third Reich. This period can be divided into three sections: 1918-1924, when the Weimar Republic was set up and survived a series of severe crises; 1924-1929, when the republic was relatively stable and prosperous; and 1929-1933, when renewed instability eventually put an end to democracy with the appointment of Hitler as Reich Chancellor on 30 January 1933.

1918-1924: Defeat and New Order Survival The defeat of 1918 hit the German public with brutal suddenness. To the very end they had been told that victory was within their grasp. In the spring of 1918 the German High Command still staked all on an offensive to achieve the breakthrough on the Western Front which had eluded them since 1914. An all-out victory would perpetuate the semi-authoritarian imperial regime and the privileges of its dominant classes. In fact German resources were by 1918 hopelessly over-stretched and morale at home and in the army had become fragile. At the end of September 1918 the High Command had to acknowledge defeat by asking for an armistice. This precipitated the revolution and the overthrow of the monarchy. The parliamentary democracy which was established in Germany in 1918/19 was therefore the consequence of defeat and revolution and not the deliberate choice of a majority of the population. They hoped, however, that the removal of the Kaiser and the adoption of parliamentary democracy would make the Allies grant Germany a lenient peace. When the terms of the treaty Versailles became public in May 1919 many who had briefly supported democracy turned against it. Others, mostly the middle classes previously loyal to the Empire, had never wanted democracy and deeply resented the overthrow of the monarchy. They persuaded themselves that the German army had never been defeated on the battlefield, but had been undermined by subversion on the home front. The men swept to power in the revolution of November 1918 were held responsible for the collapse of civilian morale and accused of betraying the Fatherland for their own ends. This was the notorious 'stab-in-the-back myth'. Democracy and the Weimar Republic were therefore never universally accepted and suffered from a lack of legitimacy. In fair weather a majority might go along with it, but in a time of hardship, as in the Great Depression after 1929, they would desert it.

Why Weimar's Failure was Not Inevitable Weimar's failure was, however, not inevitable, for the republic survived a period of severe political and economic crisis in its early years. The first threat came from the left, disappointed with the results of the revolution. They wanted a thorough-going transformation of society, as in Russia, based on the workers' and soldiers' councils which had spontaneously sprung up during the German revolution. Such a system had little chance of being realised in an advanced industrial country like Germany, where, unlike Russia, the workers had long had the vote. The first elections after the fall of the monarchy did not produce a socialist majority and the SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany) had to govern in coalition with middle-class parties. Some historians have blamed the Social Democrats led by Friedrich Ebert for being too obsessed with the threat from the left and too reliant on the old imperial officials, particularly the officer corps and the general staff. Without their help, however, Ebert and his colleagues could not have fed the population, maintained law and order and safeguarded the unity of the Reich in 1918/19. The Treaty of Versailles was regarded in Germany as humiliating and incapable of fulfilment. People lost sight of the fact that it left the unified Germany created in 1870 basically intact and in the long run in a strategically strong position, with weak neighbours on its east. Following Versailles, disillusionment with democracy led, in March 1920, to the first attempt by right-wing nationalists to overthrow the republic, the Kapp Putsch. At this point pro-republican forces, the parties of the centre and the left, were still strong enough to frustrate the coup. A general strike played a key role in defeating the plotters. In the next few years instability was aggravated by accelerating inflation. The German currency had already lost much of its value during the war and Weimar governments were too weak to bring inflation under control. The reparations which Germany was obliged to pay under the peace settlement, and which were the subject of international negotiations from 1920 onwards, gave the Reich governments no incentive to put their finances in order. Moreover, by letting inflation continue, the Germans managed for a time to avoid the post-war slump that hit the other major industrial countries, Britain and America. The French Government under Poincar‚ felt that Germany was deliberately evading reparations and in January 1923 occupied the Ruhr as a 'productive pledge'. In France the Versailles Treaty was regarded as having insufficiently safeguarded her security against German aggression and reparations provided a lever through which the French hoped to retain some control over Germany. The economic separation of the Ruhr from the Reich knocked the bottom out of the German currency. By the summer of 1923 there was hyper-inflation; wages had to be paid with washing-baskets full of banknotes and the value of the mark fell hourly. Economic life was in chaos. It looked as if Germany was about to experience the disintegration she had avoided in 1918. In Central Germany there was an attempted Communist uprising; in Bavaria right-wing extremists, led by Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist party, tried to seize power. The Nazis were one of many extreme right-wing groups whose hallmark was strident nationalism, based on the belief that Germans were an Aryan race, superior particularly to the Slav peoples of Eastern Europe. Most such groups were strongly anti-Semitic, believing that Jews were an alien race within, conspiring against the German people through ideologies such as liberalism and socialism, while as promoters of international capitalism they were undermining the economy of the country. In the social crisis of the post-war period sections of the lower middle class, squeezed between big business and labour and stripped of their savings by inflation, were attracted by National Socialism, simultaneously nationalist, anti-capitalist and anti-Bolshevik. There were similar fascist movements in other European countries, built around a leader who would impose order and authority. Hitler's movement obtained local prominence in Bavaria through his ability to give violent expression to the resentments and hatreds of people whose security had been shattered by defeat and revolution. In Bavaria the authorities dealt leniently with right-wing violence, for groups such as the Nazis might be needed against another uprising from the extreme left. Thus, Hitler and his movement grew, especially in the turmoil of 1923. He was, however, not important enough to control events and in November 1923 the Beer Hall Putsch failed ignominiously.

1924-1929: More Stability, Peace and Prosperity but Fundamental Weaknesses Remain